Thriving: Reflections for the Future Maker

Friday 4 Dec, 1:00 PM

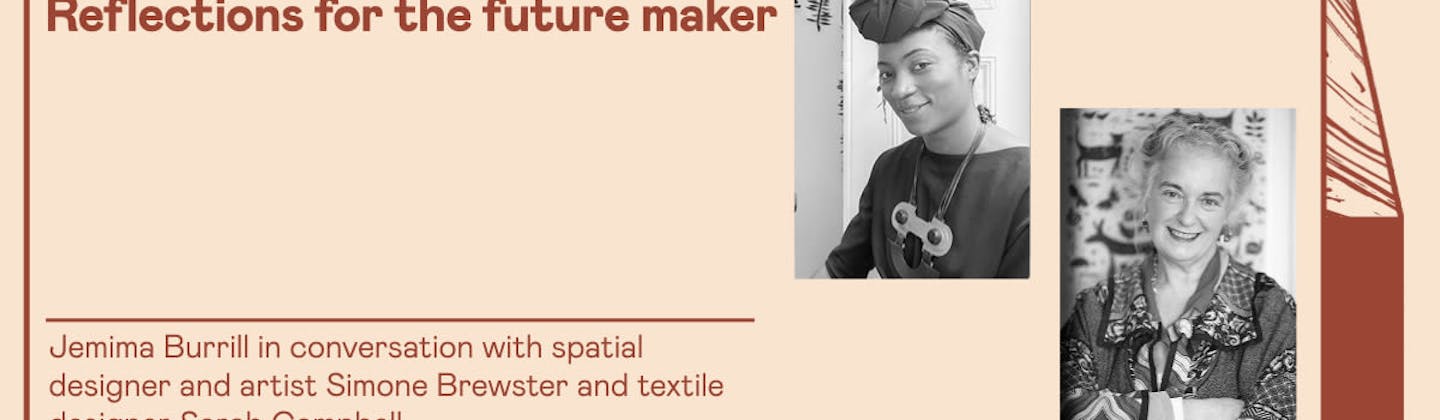

Jemima Burrill in conversation with spatial designer and artist Simone Brewster and textile designer Sarah Campbell.

Advice, expertise and knowledge - join host Jemima Burrill as she talks to spatial designer and artist Simone Brewster, with textile designer Sarah Campbell, as they share insights of their eclectic and diverse practices, as well reflecting on what future creative careers require to thrive.

A lunchtime conversation which promises to be as lively as it is multifaceted, Jemima will delve into what it means to be a designer and artist working across a wide range of media, from iPad drawings, jewellery, sculpture and painting - to furniture, textiles and copper-roller engravings. Where do such creatives find their insatiable sources of inspiration?

Simone Brewster is a London based artist creating large scale, statement sculptural furniture, objet d'art and jewellery. She holds a degree in Architecture from the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London and an MA, Design Products from the Royal College of Art. Using this she works across scales, from jewellery to furniture, and beyond. Her collections explore ‘intimate architectures’ - creating objects and spaces that utilise architectural principals throughout.

Simone's work has been exhibited at the British Embassy during the London 2012 Olympic Games as an example of British Design Talent, The Royal College of Art 175 Year Anniversary Exhibition, Collect at the Saatchi Gallery, amongst many other UK and international exhibitions.

Jemima will also be joined by internationally acclaimed textile designer, Sarah Campbell, the co-founder of the renowned design partnership Collier Campbell with her sister Susan Collier; they worked together for more than fifty years.

Verve, love of pattern and colour, and inventive freshness are the hallmarks of all Sarah Campbell’s work. Whatever the project she uniquely combines her expertise and experience with originality and joy, both serious and playful.

With this wealth of experience, varied career paths and range of influences, join host Jemima, as she uncovers how they both got to where they are today, and plans for future growth.